So You Think We Are Plants?

Lichens

A lichen is not a single organism. It is a symbiotic partnership between a fungus and either an alga or a cyanobacterium. There are thousands of fungal species involved in lichen associations but less than a hundred species of algae and cyanobacteria, so lichens are classified in the Fungal Kingdom, not the Plant Kingdom. Sometimes you will see them called lichenised fungi.

Rainforest canopy on the Lamington Plateau in Queensland. The pale green areas are trailing lichen from the genus Usnea. |

In the partnership the two organisms live together in a way that benefits both — though the benefits may not be equally shared. The non-fungal partner (or photobiont) contains chlorophyll and produces its own food. The fungus provides structural support and a fairly stable microenvironment for the non-fungal partner. Most lichens derive their shape from the fungal partner with the non-fungal cells often confined to a single layer just below the exposed surface of the lichen. The lichens also vary greatly in size, from tiny species to long, trailing species.

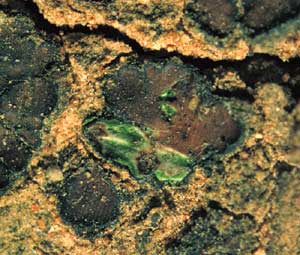

A lichen in the genus Endocarpon. In the centre of the picture there is a green area where the upper surface has been scraped away to show the underlying algal cells. |

The photobionts that occur in lichen partnerships can also be found free-living, without any fungal partner. In contrast, the fungi that are involved in these partnerships cannot survive on their own in nature. However the fungi can be grown separately in the laboratory.

Lichens are prodigious chemical factories. Lichens are known to produce more than 800 chemical compounds that are not found in any other living organisms. These compounds are produced by the lichen partnership and not when either partner is grown alone. While a number of these compounds help protect lichens against ultraviolet radiation, various microbes and herbivores, the roles of many are not yet understood.

Growth Forms

Broadly speaking lichens can be grouped into four types of growth forms.

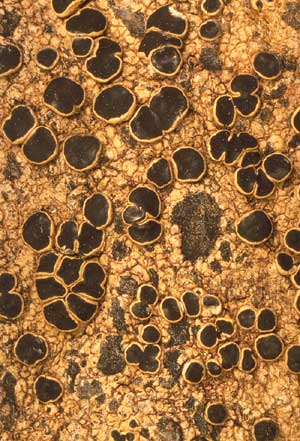

Crustose lichens look like thin crusts or washes of paint and are firmly attached over their entire underside to the surfaces they grow on.

Squamulose lichens look like small flakes or crumbs scattered across the surfaces they grow on.

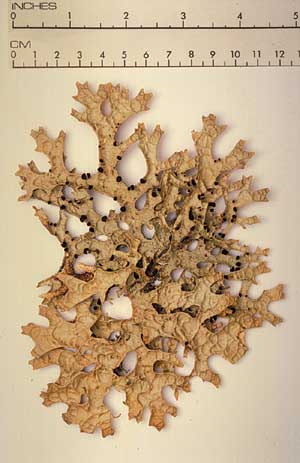

Foliose lichens have a lobed growth form. The lobes may be narrow or broad, depending on the species, and may be attached at various points on their undersides.

Fruticose lichens are erect or pendulous, markedly three-dimensional, and are attached at the base.

The fruticose lichen Cladia retipora, found on the ground in eastern Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand. |

A fruticose lichen in the genus Usnea. |

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)